Searching for a Common Language

Note, this article originally appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of Quirks. By Anna Shevalova, our head of Bazis Health and Katharina Gancarczyk, project manager.

Virtual patient communities provide people a digital space to interact and discuss their questions, fears and anxieties around various medical issues. They’re a place to learn, educate others and understand shared experiences.

For health care researchers, they serve as a goldmine of useful data. They are full of great insights about patients, diseases and medical cultures. In an effort to understand similarities and differences across different patient communities, our team read through thousands of posts. Our core question was this: What can we learn about the conditions and support systems available to patients by studying virtual patient communities across different countries?

First though, we’d like to share a few posts from virtual patient communities (VPCs) that show just how insightful they can be.

Mary is terrified of needles but finally decides to go ahead with her in vitro fertilization (IVF). In February, she writes an emotional post asking “What if it doesn’t work? What if it DOES work? Why does it have to be so difficult?” This shows the uncertainty she feels about all the pending procedures.

Jane has had Type 1 diabetes for five years now. She has a long history struggling with her self-esteem and mental health. Despite that, she encourages others: “I want other people to know they are not alone in this and that you shouldn’t feel ashamed that this is happening in your life.” She shares her experience with others, while giving lifestyle recommendations.

Layla is worried about her 7-year-old son with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). He has trouble with some everyday tasks such as using public toilets. She writes, “He can easily get distracted and doesn’t always know what to do if something unexpected happens, such as running out of toilet paper.” She asks questions on how to cope with that, also expressing her worry and uncertainty.

Three different areas

As part of our research on this topic, we looked at VPCs for these three different medical areas: in vitro fertilization, Type 1 diabetes and autism spectrum disorder. We chose these three as they span a wide range in terms of complexity of procedures and care and the timeframe for the condition (for example, IVF is a limited timeframe while autism is a lifelong condition).

To add another layer to our research, we wanted to determine the impact of a patient’s medical culture on their compliance. So we looked at the United States (we defined this as a patient-centered culture), Germany (prevalently patient-centered; something in between an individualistic and collective medical culture) and Russia (an authoritative medical culture, one that is traditionally collective with a common treatment approach for many conditions).

Once we chose our scope of research and began to dig deep into VPCs, we wanted to answer the following questions:

- What can pharmaceutical manufacturers and service providers learn from VPC data if a cross-country comparison is available?

- What are the driving forces in VPCs? What are the topics discussed most or least often among patients in these online communities?

- How can VPCs help pharmaceutical manufacturers and service providers assess patient activation?

To answer these questions, we decided to compare the biggest and most active virtual communities for the three conditions in each of the three countries according to the amount of posts we determined were connected to six constructs we defined as essential for our study. Those were:

Health literacy – the degree to which individuals can obtain, process, understand and communicate about health-related information needed to make informed decisions (McCormack, 2010). In other words, it is the level of medical knowledge an individual has and groups in the virtual community that help make appropriate health decisions.

Self-efficacy – an individual’s judgement of their ability to successfully perform a behavior (Burrell, et al., 2018). How an individual estimates his or her own abilities to perform certain actions regarding health and wellbeing.

Patient activation – someone’s knowledge, skills, confidence and behaviors needed for self-managing one’s condition or health (Hibbard et. al., 2004). To be more precise, this is everything an individual does to cope with and, if possible, overcome his or her condition.

Uncertainty – a cognitive state characterized by an awareness that one has an incomplete understanding of a situation or event (Han, 2013). This is essentially the acknowledgement from a patient that they do not fully understand a situation or, in our case, their condition and how to treat it.

Compliance – the degree of adherence of a patient to a prescribed diet or treatment and whether they return for reexamination, follow-up or treatment (McGraw-Hill, 2002). In other words, does that patient do what’s required of them by their physician?

Administrative issues – limitations and difficulties related to access to medical care, such as access to physicians or drugs. This can be anything from financial difficulties to waiting times at clinics or hospitals.

German users most active

Our initial methodology consisted of three main steps. First, we retrieved all publicly available posts made during a certain time period (January 1 through December 31, 2019). Once we gathered all the information, we realized that German users were the most active across all three conditions. Second, we intended to use pre-formulated dictionaries referring to our constructs (the six we just defined and discussed) and analyze our data in the third and final step using those dictionaries. Everything was going as planned – until we realized in our third step that we were not going to find any pre-formulated dictionaries to analyze the constructs we needed! So, we decided to take the road less traveled in order to continue our research and create those dictionaries ourselves – across several languages all at once.

We identified health literacy, self-efficacy and patient activation as the main constructs for our study. However, after an extended search, we couldn’t find a single one explicitly related to any of those three core constructs. We had a second problem: Most dictionaries for automated text analysis are written in English; there are few in German or Russian. Even the ones in English that we researched did not align with the constructs we wanted to study for this particular project. That’s why it was imperative for our team to create our own dictionaries and customize each of them by language.

Unraveled our constructs

To begin, we unraveled our constructs into their different components. For example, we assumed that patients with a high health literacy would use more numeric or medical terms or know specific drug names. Based on those elements, we designed 12 different constructs, including:

- own experience

- questions

- drug discussions

- numeric information

- recommendations about lifestyle

- frequency of physician mentions

- alternative information sources

- compliance vs. administrative issues

- uncertainty-related words

- action words

- decision words

- strong and weak modal

To create dictionaries, we started by reading samples from extracted data. We did this simultaneously in multiple languages. We were fortunate to have a team member fluent in German, Russian and English, which helped us create the dictionaries in multiple languages in parallel. At the end of this step, we had 12 topic-related dictionaries in three languages. Some dictionaries can be used across conditions and others needed to be customized by conditions (always by language but sometimes also by condition). For instance, dictionaries with action and decision words were the same and the words are applied to all conditions. Meanwhile, dictionaries with drug names varied by conditions, as the treatment differs a lot.

With dictionaries created, we were able to complete a clean comparison. Using a text-analysis program our team wrote in Python, we were able to compare our dictionaries with the original data retrieved from our VPCs. When uploading a file (or set of files) to our program coupled with a single dictionary, it would compare the words from our list to the original VPC. We then received how many words and posts belonged to each dictionary in each data file, along with more detailed statistics on each word from our words list.

We decided to focus on the percentage within post-count in our analysis for more precise and accurate results. This allowed us to omit mistakes from users who use the same words repeatedly in a single post.

We added up the posts that demonstrated our various constructs to determine the frequency for each one. Some posts in VPCs demonstrated multiple constructs, while some did not demonstrate any. Health literacy was calculated using drugs, drugs simplified, numeric, lifestyle and physician mentions. Self-efficacy was the sum of questions, lifestyle and action words. Finally, patient activation was the sum of questions, drugs, drugs simplified, action words, decision words and strong modal.

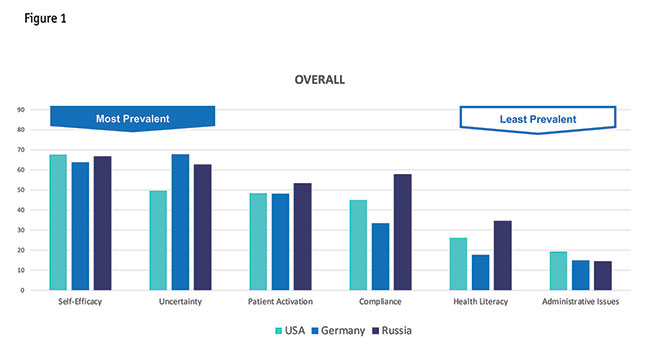

Self-efficacy and uncertainty

When looking at all posts, we discovered that self-efficacy and uncertainty were the two main constructs demonstrated across VPCs (Figure 1). The amount of self-efficacy posts is the highest in Russia and the U.S., while it is lower in Germany. Meanwhile, Germany has the highest number of posts around uncertainty, while the numbers for Russia, and especially the U.S., are significantly lower for this category.

On the other hand, there are very few posts related to administrative issues. It’s the highest in the U.S. and lowest in Russia for that category. One interesting finding: The conversations in Russian were more technical; they were using more numbers, drug names and referring to more physicians. Conversations in VPCs in the Russian language signal a higher health literacy level.

Vocabulary related to patient activation as well as compliance is used in approximately half of all posts across countries and communities. Russia showed high peaks in both categories: With 48 percent of posts containing words related to patient activation, Russia has 5 percent more than Germany and the U.S. Also, content around compliance was the highest in Russia and lowest in Germany.

When splitting the data by condition (Figures 2, 3 and 4), it is visible that patients with Type 1 diabetes are by far the most active on VPCs, while IVF patients talk about the given constructs the least. Some of the constructs such as self-efficacy and uncertainty are reflected in more than 70 percent of all the posts related to diabetes.

In vitro fertilization. Self-efficacy is the most prominent construct for IVF patients. It is reflected in 60 percent of all posts in the U.S. and in Russia, and in 57 percent of all posts in Germany. However, uncertainty is the second-most discussed topic in Germany, where it is mentioned in 54 percent of all posts. This illustrates a kind of tension: on one hand, the IVF communities demonstrate a belief they can achieve this medical goal (self-efficacy); on the other hand, the conversations on the VPCs reflect a lot of uncertainty.

Compliance is demonstrated in 53 percent of posts in the U.S. and 57 percent of posts in Russia. On the other end, administrative issues are rarely discussed among IVF patients across all countries. U.S. patients only mentioned words related to administrative issues in 11 percent of all posts, Russian IVF patients in 14 percent. Also in 18 percent of all posts German patients refer to administrative issues, which is the highest number in this section.

Type 1 diabetes. For Type 1 diabetes, self-efficacy is the most demonstrated construct, followed by uncertainty. Administrative issues is by far the least demonstrated one across all countries.

It stands out that Russian patients are the most active ones in every single category. In 80 percent of all posts in the Russian VPC words related to self-efficacy can be found. More than 60 percent of all posts mention vocabulary connected to uncertainty, patient activation and compliance.

The numbers for Russia are the highest for all topics but the difference between Russia and the other countries is the biggest for compliance and health literacy. The biggest difference is between Germany and Russia, because the numbers for the U.S. are a bit higher. Compliance for Russia is demonstrated in 64 percent of the posts; in the U.S. 38 percent and in Germany 28 percent. For health literacy, posts in Russian demonstrate this construct 59 percent of the time, in the U.S. 36 percent and in Germany 19 percent. So, the difference between Russia and Germany on those two constructs is quite significant. There is also a difference between Russia and the U.S., but one that is not as significant.

Autism spectrum disorder. Uncertainty is the most discovered construct for patients posting in autism spectrum disorder communities, something that stands out to us. Seventy-eight percent of all German posts in the VPCs on autism spectrum disorder contain uncertainty-related words, not much higher than the 71 percent of Russian posts and 65 percent of those in the U.S. Only in the U.S. did posts relating to self-efficacy remain higher like in our overall findings. On the other hand, administrative issues were the least-measured construct in ASD communities. The U.S. showed a comparable high number of posts highlighting administrative issues – 27 percent. No other construct had more than 20 percent of posts relating to administrative issues.

Here are some of our main takeaways from our research into VPCs:

- A number of posts reflected both self-efficacy and uncertainty, indicating a kind of tension across communities. Patients demonstrate a belief online they can achieve a medical goal (self-efficacy) but reflect a lot of uncertainty within the conversations they are having in community.

- Surprisingly, patients don’t discuss administrative issues that much, regardless of country or health care system.

- The level of health literacy reflected in these communities jumps around a lot. Some of these communities have a completely different level of health literacy in their respective VPCs.

- There are no dictionaries (until now!) that can detect health literacy, self-efficacy and patient activation in texts written in any language (English, German and Russian). Because languages are different and specific, you need to take a customized approach when creating dictionaries for the same construct in different languages.

Holistic approach

This methodology can be integrated with traditional research methods to provide a more holistic approach when conducting research. This is a way to obtain quantitative insights about conditions – it offers a platform and guidance for when researchers or organizations are looking to develop tools and surveys, particularly in multicountry studies.

For example, let’s say you are developing a survey to study an IVF drug across several countries. Doing a quick quantitative sweep of constructs more prevalent in IVF communities in a given country would help you as a researcher to tailor your survey. You can better address issues that already exist in a given country. In short, you have a kind of baseline for your survey you wouldn’t otherwise.

Perhaps the most exciting thing about this kind of framework is it can be replicated across a number of other languages, VPCs, medical conditions and more. We can expand with more constructs to measure patient-centered issues because these online communities are inherently patient-centered. It gives us useful insights into patients’ perspectives.

A special thanks to Tatiana Barakshina, who was our mentor along the path. We’d also like to thank Bob Spoerl, Dmitry Reshetar and Anton Skripin for their contributions.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.